AI autonomy and computing power may determine the future of jobs.

While technological advances have unsettled labor patterns throughout history, the advent of artificial intelligence (AI) has put knowledge workers on alert because of its potential to automate all sorts of creative, cognitive work.

From writing and designing to coding, teaching and conducting scientific research, jobs that had been largely shielded from previous automation waves are now being re-imagined.

A paper by IESE professors Enrique Ide and Eduard Talamas develops a framework for understanding how AI may impact the knowledge economy by considering the crucial elements of AI autonomy and the availability of computing power.

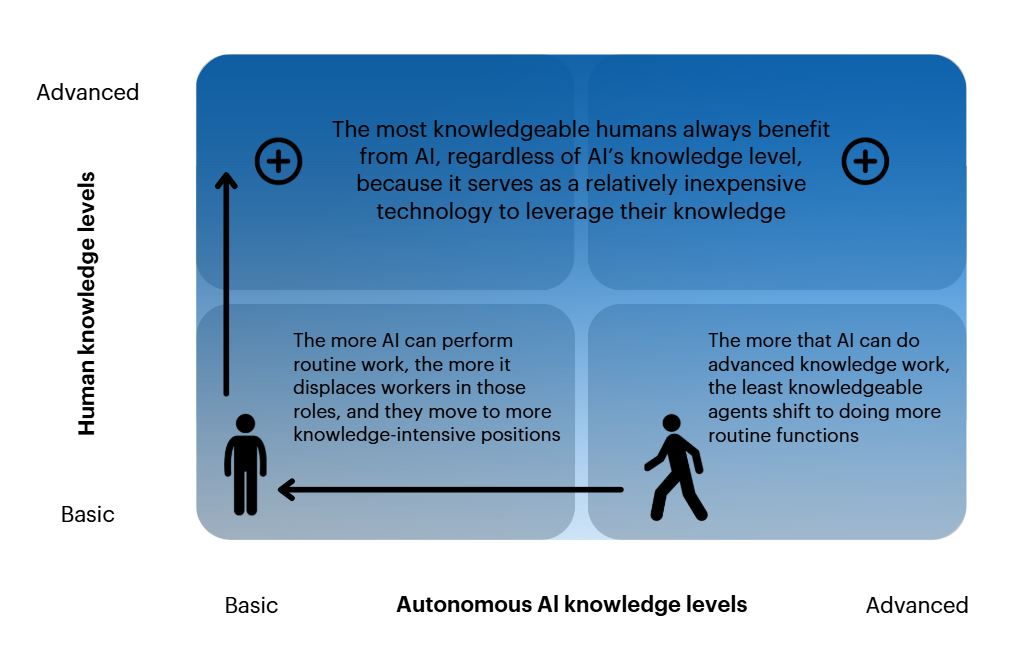

The research finds that while the most knowledgeable workers will always benefit from AI as a tool to leverage their expertise, for less knowledgeable workers the outlook is more nuanced. While they may become more productive using basic AI, their jobs may come under threat if AI becomes highly advanced in its intelligence, and computing power makes it widely available. All of these movements have profound implications for how companies are organized.

The knowledge economy before artificial intelligence: time and expertise

To begin, it’s useful to consider the knowledge economy before AI. The knowledge economy consists of all those economic activities in which time and expertise are major inputs in production — in other words, most activities in the modern economy.

For example, the main inputs in the legal services industry are the time and expertise of lawyers and paralegals, while the main outputs are essentially solutions to legal problems, in the form of legal advice and representation.

The growing importance of knowledge work in the modern economy implies that the capacity to adapt and solve problems — knowledge — is increasingly valued.

But time and knowledge are scarce and, as a result, organizations often adopt pyramidal hierarchies to economize on these resources. Returning to the legal example, law firms usually employ several associate lawyers per partner. Associates typically focus on relatively routine legal problems, allowing partners to use their expertise to solve the most important cases.

There’s another mechanism at work, which economists call positive assortative matching. Better associate lawyers tend to work with better partners, because it’s mutually beneficial. That means more knowledgeable individuals are more productive and earn more, not only because they can solve more problems but also because they work in better organizations.

Non-autonomous AI: human intervention and productivity gains

If we think of AI as an algorithm that uses computing power to automate knowledge work, its potential to impact the knowledge economy becomes readily apparent.

AI can roughly be divided along autonomy lines. Non-autonomous AI lacks the ability to operate independently and, hence, always requires human assistance to be able to produce knowledge work. Autonomous AI solves problems with only minimal human intervention.

Non-autonomous AI can only collaborate with humans, and labor productivity is greatly enhanced as a result. This synergy ensures that human labor remains essential, particularly in assisting AI in those contingencies where human-like intelligence is required. This results in humans moving into roles complementary to AI rather than being replaced by it.

The introduction of non-autonomous AI may still generate disparities in wages. Individuals with higher knowledge levels benefit more, as they can better assist AI and handle more complex problems. Over time, as AI technology improves, wages across the entire knowledge distribution can increase, leading to widely shared prosperity.

Autonomous AI: basic or advanced knowledge

The labor outlook becomes more complex when considering autonomous AI, or AI that is indistinguishable from human intelligence and can solve problems with minimal human assistance. The realism of this scenario is hotly debated and may vary by industry.

The impact of autonomous AI on knowledge work depends on whether its knowledge is relatively basic (i.e., it can mimic humans that perform routine knowledge work) or advanced (i.e., it can mimic humans that perform specialized problem-solving).

Consider first an AI that can mimic the tasks of an average legal associate (i.e., a relatively basic AI). Introducing such AI effectively increases the supply of legal associates, reducing their wages and increasing the demand for more specialized problem-solving (i.e., legal partners). As a result, the most knowledgeable associates become partners, so AI’s introduction displaces humans from routine roles to more knowledge-intensive positions. In other words, AI increases the knowledge content of human work.

This occupational displacement implies that, in this case, the introduction of AI leads to smaller, less productive and more centralized organizations. Why? Because the knowledge of the best associates is lower post-AI than pre-AI, leading to a decline in the quality of the legal associates at the best legal firms, and increasing centralization. In addition, the knowledge of the least knowledgeable partners is also lower post-AI than pre-AI, and hence, the productivity of the least productive firms is also lower.

The effects of AI are substantially different when AI is sufficiently advanced that it can mimic those higher in the knowledge hierarchy. In this case, AI decreases the knowledge content of human work, leading to larger, more productive and more decentralized firms. For instance, an AI assistant automating specialized customer support effectively reduces the scarcity of these agents, forcing the least knowledgeable among them to shift to routine customer support.

Irrespective of whether AI is basic or advanced, its introduction increases total labor income, but it necessarily creates winners and losers in the labor market. In particular, the least knowledgeable humans benefit when AI’s knowledge is high because its introduction gives them access to better and/or less expensive solvers. The most knowledgeable humans, in contrast, always benefit from AI — regardless of AI’s knowledge level — because it serves as a relatively inexpensive technology to leverage their knowledge.

Will AI destroy jobs in the knowledge economy?

In this framework, for highly knowledgeable workers, even when AI is autonomous, the labor of humans who are more knowledgeable than AI is never redundant — as they can always specialize in tackling problems that AI cannot solve.

Whether the labor of humans who are less knowledgeable than AI is redundant depends on how large the available computing power is relative to its potential applications.

On the one hand, if AI’s potential applications remain large relative to the available compute, then no one’s labor is made redundant by AI. All individuals who are less knowledgeable than AI do routine work (either assisted by other humans or by AI) because that is their comparative advantage: They are less likely than AI to succeed on their own, so it is more valuable for them to receive assistance. In fact, if AI is sufficiently good, the introduction of AI can benefit the least knowledgeable workers.

On the other hand, if compute becomes sufficiently abundant, autonomous AI may lead to the unemployment of workers whose knowledge is below AI’s. For example, if the healthcare industry had sufficient computing power at its disposal to screen every medical issue exclusively via AI, then human healthcare providers who have less knowledge than AI would naturally become redundant.

This has profound implications not only for employees — who must consider their knowledge and skill sets vis-a-vis AI — but also for the organization of the firm. There are no easy answers to AI’s impact on jobs, but considering AI’s relative autonomy and the availability of computing power may help to provide some direction.